Creative Myths of Cambridge

A talk delivered to the Rupert Brooke Society, August 19th, 2012

© William Pryor

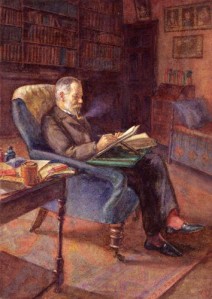

In a letter to my grandfather not long before his death in 1925 from multiple sclerosis, Virginia Woolf wrote: Is your art as chaotic as ours? I feel that for us writers the only chance now is to go out into the desert & peer about, like devoted scapegoats, for some sign of a path. I expect you got through your discoveries sometime earlier.

In a letter to my grandfather not long before his death in 1925 from multiple sclerosis, Virginia Woolf wrote: Is your art as chaotic as ours? I feel that for us writers the only chance now is to go out into the desert & peer about, like devoted scapegoats, for some sign of a path. I expect you got through your discoveries sometime earlier.

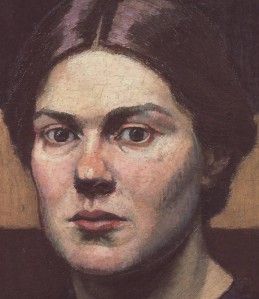

But he wasn’t a writer; he had told her he was writing an autobiography which was enough for her to generously include him in the clan of authors, of devoted scapegoats. Rupert Brooke, my grandmother Gwen Raverat, my cousin Frances Cornford and my friend Syd Barrett all went out into the desert, peering about for some sign of a path. They all found their own creative path. They all went through the minefields of mental mutability to get there. They all held Cambridge as the crucible of their creativity. They all meddled in myth.

For those of you for whom the popular culture of the last 50 years has been so much froth on the pond of time, Syd Barrett was the singer with the psychedelic rock n roll band, Pink Floyd. They are almost an industry in their own right: their lead guitarist David Gilmour is reputed to be worth in excess of £85m.

But before I go any further I should say that, as you may already have detected, what I am laying before you today is not in any sense an academic treatise, nor even a cogent essay, but more a prose poem ambling towards its own kind of scapegoat myth.

Virginia Woolf, a friend of Rupert, Gwen and to a lesser extent Frances, also knew the dark recesses of what was probably a bipolar disorder. Virginia wrote: As an experience, madness is terrific… and in its lava I still find most of the things I write about.

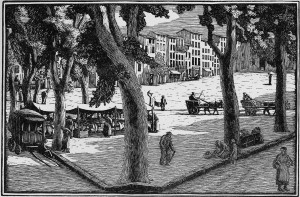

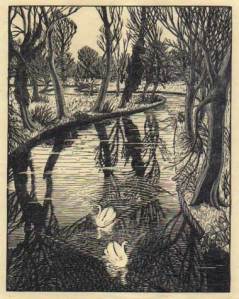

We don’t think of Rupert, Gwen, Frances, Virginia or even Syd as mad people, but as artists. They found their art or rather their attitude, their vision of their art, in the lava, the fluorescence of their experience of breakdown, madness, depression – call it what you will. I don’t mean to overstate the importance of their mental condition (though it drove one of them to suicide, one to spend years in “homes”, another to live 40 years in virtual isolation, and my grandmother to produce more incisive wood engravings) just to note that it was there. And the myth of the creative genius doesn’t work without a reasonable dose of sociopathic aberration.

Frances Cornford’s famous lines about Rupert Brooke are very helpful to my ramblings here:

Frances Cornford’s famous lines about Rupert Brooke are very helpful to my ramblings here:

A young Apollo, golden-haired,

Stands dreaming on the verge of strife,

Magnificently unprepared

For the long littleness of life.

The long littleness of life is precisely what Rupert, Gwen, Frances and Syd were digging worm holes through. They became myths precisely because each of them showed us transcendence in the littleness, the quotidian of life.

Myths are public dreams, dreams are private myths, said Joseph Campbell. Myths are not untruths; rather they are stories that explain the inexplicable; they are truths, but mysterious ones. Jean Cocteau said: Man seeks to escape himself in myth, and does so by any means at his disposal. We create myths and romance to escape the humdrum, to know a deeper truth about ourselves. Rupert, Gwen, Frances and Syd all have their mythologies; they take us to a better past, golden days of first loves, skinny dipping, poems, beauty, songs, creativity and transcendence.

To fulfil the function of a myth so that one is built around you, it is necessary to act it out, to become a god with a smallest ‘g’. Rupert and Syd ticked all the boxes: they were beautiful, passionate and creative gods who were struck down in their primes. In a very short time, they shot from local celebrity to breaking hearts on a national, even international, scale.

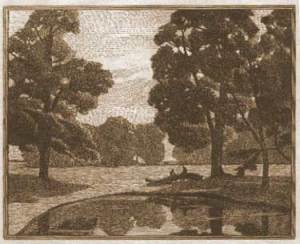

My grandmother’s story was different, but mythic none the less. With her it was always her wood engravings and then Period Piece that took the stage, not her. As were poems for Frances. But the art of all four shared one trait: nostalgia for a past that might have existed, but probably didn’t; a past where loves were complicated but intense, landscapes always romantic and well-kept and childhoods always playful.

The Industrialisation of Myth

And Grantchester has become mythic simply because it occupies a corner of so many imaginations that will always be England, poetry and pubs called The Rupert Brooke. The pub’s website has this: Where better than overlooking the outstanding beauty of Grantchester meadows, to have a truly English vintage cream tea. Our cream teas are available between Ten to 3 & 6 everyday, as well as to all weddings, functions and corporate events. The eclectic mix and match style of crockery will add a refreshing touch of vintage charm to any occasion.

The industrialisation of myth; corporate events from ten to three; myths not only explaining the inexplicable but selling some cream teas on the way! The penetrating power of what Rupert, Gwen, Frances and Syd did lies in how they present that quintessentially English nostalgia, how they transmitted it. With none of them was it ever commercial, cloying, clichéd or cluttered with sentiment. Rupert’s was shot through with anger; Gwen’s with incisive observation and a mastery of detail; Frances’s with melancholy and a deceptive simplicity; Syd’s with an originality of whimsy and musical rule-breaking. None of them were avant-garde; all of them were consummate practitioners of their crafts.

My grandmother’s cousin Ralph Vaughan Williams, 13 years her senior, composed music that shared many of the same qualities as Rupert and Frances’s poems, Gwen’s art (and even, oddly, Syd’s songs): quintessentially English, lyrical, angry, tragic, startling, grand, mythic. In The Origins of the English Imagination, Peter Ackroyd writes: If that Englishness in [his] music can be encapsulated in words at all, those words would probably be: ostensibly familiar and commonplace, yet deep and mystical as well as lyrical, melodic, melancholic, and nostalgic, yet timeless.

My grandmother’s cousin Ralph Vaughan Williams, 13 years her senior, composed music that shared many of the same qualities as Rupert and Frances’s poems, Gwen’s art (and even, oddly, Syd’s songs): quintessentially English, lyrical, angry, tragic, startling, grand, mythic. In The Origins of the English Imagination, Peter Ackroyd writes: If that Englishness in [his] music can be encapsulated in words at all, those words would probably be: ostensibly familiar and commonplace, yet deep and mystical as well as lyrical, melodic, melancholic, and nostalgic, yet timeless.

Rupert, Gwen, Frances and Syd needed to overthrow their family backgrounds so they could absorb all that was true in their heritage. As George Bernard Shaw said: If you cannot get rid of the family skeleton, you may as well make it dance. The black sheep danced, realizing that most of the rest of the flock had been piebald, if not black, all along. After all Dodie Smith described the family as ‘that dear octopus from whose tentacles we never quite escape, nor in our innermost hearts never quite wish to’. Rupert had to escape the Ranee; Gwen had to persuade her father George Darwin to let her become one of the first women to study art at the Slade; Frances had to battle through her depression, which was almost certainly a learned Darwin response to the littleness of life; Syd had to transcend the middle-class stodginess of his academic Cambridge family.

It didn’t matter how liberal and indeed enlightened their families were, there was still the need for revolution. Gwen would hold the Darwin clan up for mild but deeply fond ridicule in her description of a picnic held to celebrate her cousin Frances’s marriage to Francis Cornford: It was a grey, cold, gusty day in June. The aunts sat huddled in furs in the boats, their heavy hats flapping in the wind. The uncles, in coats and cloaks and mufflers, were wretchedly uncomfortable on the hard, cramped seats, and they hardly even tried to pretend that they were not catching their deaths of cold. But it was still worse when they had to sit down to have tea on the damp, thistly grass near Grantchester Mill. There were so many miseries which we young ones had never noticed at all: nettles, ants, cow-pats. . . besides that all-penetrating wind. The tea had been put into bottles wrapped in flannels (there were no Thermos flasks then); and the climax came when it was found that it had all been sugared beforehand. This was an inexpressible calamity. They all hated sugar in their tea. Besides it was Immoral. Uncle Frank said, with extreme bitterness: ‘It’s not the sugar I mind, but the Folly of it.’ This was half a joke; but at his words the hopelessness and the hollowness of a world where everything goes wrong, came flooding over us; and we cut our losses and made all possible haste to get them home to a good fire.

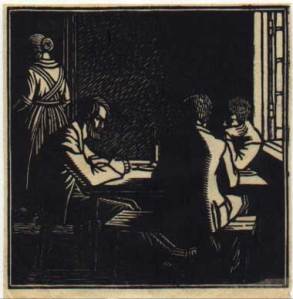

The art of all my subjects was made on a ground of family circumstance, a bed of dysfunctionality. Mostly they could not talk about their art, they had simply to do it. Jean Cocteau said: An artist cannot speak about his art any more than a plant can discuss horticulture. But he can talk about the circumstances, the milieu, the hothouse in which his art happens. It is not clear precisely when, but probably in the late 1920s, my grandmother thought she might try her hand as a novelist, encouraged, no doubt by the early success of her friend Virginia Woolf. Though it needed work, her first unnamed attempt captured the romance of the group of young romantics Virginia had labelled the Neo-Pagans:

We met, we found we had many ideas in common; we found that we could talk. And so we talked from morning to night and from night till morning, and for the first two years we did practically nothing else. We had been shy and diffident; we had wondered if anyone had ever had such ideas as ours before; we had wondered if they could possibly be true ideas; if there was the remotest chance that we could be worth anything. Now, when we came together many of our doubts disappeared; we were passionately convinced of the truth and splendour of our thoughts; we felt that we were quite different from our fathers; all our ways of thinking and our opinions seemed bold and new. And though each of us alone might still doubt his own powers, we each thought that never before had there met together a group of such fine and intelligent young men. I think that we each thought ourselves singularly happy in having such wonderful friends.

From the beginning it was from Rupert that we expected great things; it was Rupert we all watched and loved. Perhaps the most obvious thing about him was his beauty. He was not so beautiful as many another man has been, and yet there was something in his appearance, which it was impossible to forget. It was no good laughing at him; calling him pink and white, or chubby; saying his eyes were too small or his legs too short. There was a nobility about the carriage of his head and the shape of it, a radiance in his fair hair and shining face, a sweetness and a secrecy in his deep set eyes, a straight strength in his limbs, which remained for ever in the minds of those who once had seen him; which penetrated and coloured every thought of him.

I remember those first two years as long days and nights of talk; talk, lying in the cow parsley under the great elms; talk in lazy punts on the river; talk round the fire in Rupert’s room; talk which seemed always to get nearer and nearer to the heart of things. It was best of all in the evenings in Rupert’s room. He used to lie in his great armchair, his legs stretched right across the floor, his fingers twisted in his hair; while Jacques sat smoking by the fire, continually poking it; his face was round and pale; his hair was dark. We smoked and ate muffins or sweets and talked and talked while the firelight danced on the ceiling, and all the possibilities of the world seemed open to us.

For a time we were very decadent. We used to loll in armchairs and talk wearily about Art and Suicide and the Sex Problem. We used to discuss the ridiculous superstitions about God and Religion; the absurd prejudices of patriotism and decency; the grotesque encumbrances called parents. We were very, very old and we knew all about everything; but we often forgot our age and omniscience and played the fool like anyone else.

The extraordinary thing about this passage is how vividly she also conjures up the best bits of my youth, let alone hers and Rupert’s. Gwen gave us grandchildren a wooden Canadian canoe which was kept in the boathouse under the gallery at The Old Granary, now part of Darwin College. My Norwegian fellow grandson, Christian Hambro, and I would paddle down to the Backs and capsize it on purpose just to alarm the tourists. I would venture on day-long treks to the source of the Cam at Haslingfield. We would loll in punts and talk and talk. The Sex Problem had disappeared, this being the sixties.

Syd Barrett was the Rupert of our circle. Syd would join us to punt up to Grantchester, strumming his guitar, singing his whimsical songs influenced by Hillaire Belloc, Edward Lear, Tolkein and even, perhaps, Frances and Rupert. We too were decadent. We too were in the business of the overthrowing of parents. We had so much to reject: war, atom bombs, privilege.

Syd Barrett was the Rupert of our circle. Syd would join us to punt up to Grantchester, strumming his guitar, singing his whimsical songs influenced by Hillaire Belloc, Edward Lear, Tolkein and even, perhaps, Frances and Rupert. We too were decadent. We too were in the business of the overthrowing of parents. We had so much to reject: war, atom bombs, privilege.

From the beginning it was from Syd we expected great things; it was Syd we all watched and loved. Perhaps the most obvious thing about him was his beauty. And his impenetrable creative certainty. A very short time later he joined the band that became Pink Floyd as its lyricist leader and burst into worldwide fame for just 18 months. As his behaviour got more and more unacceptable, even for a rock star, in 1968 the band indecorously pushed him aside. He walked back to Cambridge and retired to a life as a painter recluse, living with his mother, wanting nothing to do with the legend he had once been. He died 38 years later aged 60 in 2006.

Both Rupert and Syd struck down in their youth like James Dean. Both Rebels without a clear Cause; both making art that takes us back to a past that never really existed. We just feel it ought to have.

Pink Floyd needed a mythology of Syd to expiate guilt and romance their origins and so wrote and performed songs about him (Wish You Were Here and Shine On You Crazy Diamond) which then made Syd a global myth. I mean myth in the sense of a story that explains the inexplicable, a story of gods and goddesses; not in the sense of an untruth.

So did my grandmother, my great uncle Geoffrey Keynes, Frances and most of the neo-pagans need a mythology of Rupert. They made a beautiful edition of his poems to which Gwen contributed two lyrical wood engravings. An Apollo who died so young and so absurdly had to be a god of the romantic ideal. They forgot all the exasperating complexity of his unrequited loves.

There may be those who would dismiss any parallel between a band of rock n rollers and Rupert’s neo-pagan and Bloomsbury high-flyers. They would be wrong. In Grantchester Meadows, Pink Floyd’s bass player, Roger Waters, who grew up in Cambridge, captured the nostalgie de la jeunesse that Rupert initiated with his poem – the parallels are striking:

Icy wind of night be gone

This is not your domain

In the sky a bird was heard to cry

Misty morning whisperings

And gentle stirring sounds

Belied the deathly silence

That lay all around.

Hear the lark and harken

to the barking of the dog fox

gone to ground

See the splashing of the kingfisher flashing to the water

And a river of green is sliding

Unseen beneath the trees

Laughing as it passes

Through the endless summer

Making for the sea

In the lazy water meadow

I lay me down.

All around me golden sunflakes

Settle on the ground.

Basking in the sunshine

Of a bygone afternoon

Bringing sounds of yesterday

Into this city room

Hear the lark and harken

To the barking of the dog fox

Gone to ground

See the splashing

Of the kingfisher flashing to the water

And a river of green is sliding

Unseen beneath the trees

Laughing as it passes

Through the endless summer

Making for the sea

In the lazy water meadow

I lay me down

All around me golden sunflakes

Covering the ground

Basking in the sunshine

Of a bygone afternoon

Bringing sounds of yesterday

Into my city room.

Hear the lark and harken

To the barking of the dog fox

Gone to ground

See the splashing

Of the kingfisher flashing to the water

And a river of green is sliding

Unseen beneath the trees

Laughing as it passes

Through the endless summer

Making for the sea

Romantic, but effective nostalgia through and through. Indeed Roger’s words can be read as a direct descendant of lines like:

I only know that you may lie

Day long and watch the Cambridge sky,

And, flower-lulled in sleepy grass,

Hear the cool lapse of hours pass,

Until the centuries blend and blur

In Grantchester, in Grantchester. . .

Nothing too abstract, surreal or whimsical in either of these, unlike Syd’s lyrics for Bike:

I’ve got a bike

You can ride it if you like

It’s got a basket

A bell that rings

And things to make it look good

I’d give it to you if I could

But I borrowed it

You’re the kind of girl that fits in with my world

I’ll give you anything

Everything if you want things

I’ve got a cloak

It’s a bit of a joke

There’s a tear up the front

It’s red and black

I’ve had it for months

If you think it could look good

Then I guess it should

the last few lines are telling:

I know a room full of musical tunes

Some rhyme

Some ching

Most of them are clockwork

Let’s go into the other room and make them work.

Compare Rupert’s nostalgia for Grantchester with Frances Cornford’s in the last two stanzas of her Cambridge Autumn, written some 22 years and a world war after Rupert wrote his ode to Grantchester:

O, I must raise myself and go, for now

The sun sinks down, and that old labourer,

that simple vision by the cottage door

Which morning brought, returns; who soon must fare

Alone into the dark of death, no more,

Like this unconquered planet, to emerge

On crystal April light, with daffodils.

His strange, eternal spring shall be elsewhere,

Only the dead can tell how clear, and fair,

And certain as the look their faces bear

After the storm and ravage. Yet it seems

Though all creation shares the departing light –

Red cows and robins, and rooks in flight,

And the great barns – that most of all to those

Old, patient eyes no temporal spring shall bless,

This vast, warm, earthly autumn tenderness

Is come to say Amen, before they close.

Death haunts her hymn to the great barns of Cambridgeshire; it is almost a mourning for a lost Cambridge. For Gwen, Frances, Rupert and Syd, Cambridge and Grantchester inspired a bursting creativity that could not be held back and acted as a magnet. A creativity that is a matter of life or death to all these myths of creativity.

Gwen wrote in 1924 to her cousin Nora Barlow: [It is] a matter of life and death to keep going at [my painting and drawing] as much as I can and not lose hold. I feel I’ve got something in me of which I only get a millionth part, partly from lack of time and leisure of mind (by my own unregretted choice in marrying and having children), partly from things in one’s own self getting in the way and in between…

Stressed with looking after two small girls (my mother and aunt) and a dying husband, she still feels it is a matter of life and death to not lose hold of her creative process. Syd and Rupert sacrificed themselves on this same altar. It is the myth of the hero transcending the ordinary. Gwen said of wood engraving it was “hard, tight, definite” with “no possible room for vagueness”. Maybe she means that it is the looking, the seeing that matters. William Carlos Williams, when explaining his poetics, said that there are no ideas but in things.

Gwen wrote: All good painting is religious in that it is done in the religious spirit: that the painter feels it is the most important thing in the world: a thing worth doing for itself, even if no one were ever to see it. In this sense art is religion. But it is not the subject of a picture which matters, it is the feeling with which the subject is approached.

The nostalgia Rupert, Gwen, Frances and Syd express is the weltschmerz of being alive; a keening Frances evinced so clearly in her poem, After the Eumenides, in the collection Mountains and Molehills that Gwen illustrated in 1934:

Long ago, in stony Greece,

The human heart knew no peace.

In its darkness it was torn,

And cursed, as now, the fate of being born;

And tried to heal its agony with song.

O Lord, how long?

A poem I wrote that plays a key part in my screenplay COOL (which finally looks like it might get realised before I die) is my attempt to express the same melancholia of youth, youngness, that concerned Rupert, Frances and Syd and which Gwen somehow transcended:

Long Burgeons

Long burgeons the last cello

swells with cut enthusiasms

where bud the swollen flowers

of being young

this grave

mistaken incursion

this death

into life.

long purposes frolicking in the surf

short of the shore, the beach

between life and death.

The beach between life and death is where the artist tries to heal his agony with a song while his ambitions, his purposes frolic in the surf. After all, it is death that gives meaning to life, death that powers myths. Where would Syd and Rupert be if they hadn’t burned out so young?

Marcel Duchamp (of urinal fame) said: To all appearances, the artist acts like a mediumistic being who, from the labyrinth beyond time and space, seeks his way out to a clearing. Millions of artists create; only a few thousands are discussed or accepted by the spectator and many less again are consecrated by posterity.

Syd and Rupert have been consecrated; Gwen and Frances less so, largely because they worked in smaller arenas. Syd & Rupert have become icons, myths, gods of youth, innocence and idiosyncrasy. Forever reconsecrated when David Gilmour sings Shine On:

Remember when you were young,

You shone like the sun.

Shine on you crazy diamond.

Now there’s a look in your eyes,

Like black holes in the sky.

Shine on you crazy diamond.

You were caught on the crossfire

Of childhood and stardom,

Blown on the steel breeze.

Come on you target for faraway laughter,

Come on you stranger, you legend, you martyr, and shine!

You reached for the secret too soon,

You cried for the moon.

Shine on you crazy diamond.

Threatened by shadows at night,

And exposed in the light.

Shine on you crazy diamond.

Well you wore out your welcome

With random precision,

Rode on the steel breeze.

Come on you raver, you seer of visions,

Come on you painter, you piper, you prisoner, and shine!

Just two years in the limelight, but here we are, forty years later, still talking about him. We were the first teenagers, back then – previously people went straight from childhood to young adulthood in their bowler hats or pinnies – and Syd, authentic, beautiful, witty, musical and idiosyncratic Syd was much more than most teenagers knew how to be. Both he and Rupert embodied what we could all be. Syd got paid to be himself, or the leprechaun he constructed.

The essence of Syd was his creativity; the gift that Pink Floyd were to turn into a commodity worth many millions. A gift that flows all the time for all of us, could we but know it, grasp it, ride it.

We project our intricately woven fabric of self and for some of us this projecting is art. It is public. People buy into it. It is performance. We then buy into this our own projection ourselves, just as we bought into the fabric from which it was woven. As Syd sang in Jugband Blues: It’s awfully considerate of you to think of me here; and I’m much obliged to you for making it clear – that I’m not here.

The projecting, the loving of talent, the glimpses of godhood – all this is addictive – we want more, even though we know it is bad for us, for the central stability of the self. Syd’s fame gave him permission to transgress, to explore beyond sanity. He had the authority of one who was making the gift of creativity live in front of our eyes and ears.

Gwen wrote so simply in Time & Tide in 1934: Painting is the product of the thing seen (whether with the inner eye or the outer eye makes no matter) and the passion felt about it. Representational art is on the whole greater than abstract art, partly because it is difficult to have so primitive and passionate a feeling about a cube as about a cow; but also because the eye turned outwards constantly replenishes and enlarges the symbolic imagery of the mind; while the abstractist, his eye turned inwards, allows his images to grow poorer and fewer by inbreeding.

But it does depend how you see. Gwen describes her perception as a young woman thus: Of course, there were things to worship everywhere. I can remember feeling quite desperate with love for the blisters in the dark red paint on the nursery window-sills at Cambridge, but at Down there were more things to worship than anywhere else in the world.

LSD may not have been the source of Syd’s creativity, but he came to rely on it and, all too soon, he was outcaste, scapegoated by it, by the very visions that had at first inspired him.

Antonin Artaud, the Theatre of Cruelty guy, had this to say about creativity: No one has ever written, painted, sculpted, modelled, built, or invented except literally to get out of hell.

The power, insistence and poetry of the art of Rupert, Gwen, Frances and Syd was probably no different; for Gwen and Frances it arose from their struggle to acknowledge and absorb their inner demons, while Syd’s short-lived blossoming seemed like revelation visited from a sugar cube, making it hard for him to own it. Maybe the difference might not be so important – they would all find their uninspired states unbearable. They had to create to escape hell, as Antonin Artaud well understood, and when they couldn’t escape, Virginia Woolf drowned herself, Gwen and Frances became clinically depressed and Syd retreated into chemical martyrdom.

The myths of Rupert, Gwen, Frances and Syd are stories of the god of creativity made human and the prices that must be paid. I have been in love with improvisational music making ever since I would dabble on my mother’s Steinway in our home in Chaucer Road, not more than a couple of miles from here. Even though it is not really a spectator sport, completely free improvisation is the shortest cut to the nirvana of creativity and the poem I wrote about it in 1981 is an attempt – in my Black Mountain minimalist style – to open that window a tad:

improvisation – music

not ‘made up’ as you go

not ‘found’ pre-existing

but extension. Mind

extended to include & release.

immanence.

cat’s leap for the window

is the thought of it.

as blind men know through sticks

what surrounds them

we sound what we do

through instruments

& how is the interaction

tasting – an exchange

in formation

as talk is express

is connect is

partsong

partlisten

Sylvia Plath wrote: And by the way, everything in life is writable about if you have the outgoing guts to do it, and the imagination to improvise. The worst enemy to creativity is self-doubt.

And Charles Mingus said: Creativity is more than just being different. Anybody can play weird; that’s easy. What’s hard is to be as simple as Bach. Making the complicated simple, awesomely simple, that’s creativity.

But how do we make the complicated simple? The only enemy to creativity is self-doubt. The Gift is showering down all the time, kept from us by self-doubt and consequent lack of discrimination. The act of creativity is the act of a god, but the ever-hovering self-doubt wants for it to be consecrated by posterity, for others to applaud, to pay money. It wants to overcome its scapegoat status by the consecration of fans, critics and customers, by commoditising the Gift of creativity. But in so doing the artist becomes even more of a scapegoat, taking on both the aspirations and the fears of his audience, literally loaded with their troubles and sacrificed ‘beyond the pale’ of the community.

Gwen and Virginia sum up Rupert

In March, 1925, just two weeks after Jacques died in Vence from MS, Virginia wrote a long letter to Gwen. In it she summed up Rupert rather well: I feel that Jacques was thinking a great deal of Rupert at the end. Rupert was a little mythical to me when he died. He was very rude to Nessa once; & Leonard, I think, rather disliked him; in fact Bloomsbury was against him, & he against them. Meanwhile, I had a private version of him which I stuck to when they all cried him down, & still preserve somewhere infinitely far away – but how these feelings last, how they come over one, oddly, at unexpected moments – based on my week at Grantchester [in 1911], when he was all that could be kind & interesting & substantial & downhearted (I choose these words without thinking whether they correspond to what he was to you or anybody). He was, I thought, the ablest of all the young men; I did not then think much of his poetry, which he read aloud on the lawn; but I thought he would be Prime Minister, because he had such a gift with people, & such sanity, & force; I remember a weakly pair of lovers, meandering in one day, just engaged, & very floppy (A.Y. Campbell & his bride who now writes on Shelley). You know how intense & silly & offhand in a self-conscious kind of way the Cambridge young then were about their loves – Rupert simplified them, & broadened them, – humanised them – And then he rode off on a bicycle about a railway strike. Jacques says he thinks Rupert’s poetry was poetry. I must read it again. I had come to think it mere barrel organ music, but this refers to the patriotic poems, & perhaps is unfair: but the early ones were all adjectives & contortions, weren’t they? My idea was that he was to be member of Parliament, & edit the classics: a very powerful, ambitious man, but not a poet. Still all this is no doubt wholly & completely wrong.

On the 22nd of April 1925, Gwen replied to Virginia. The letter has this: You’ve missed one point about Rupert: that he didn’t really care about life. He was ambitious but he didn’t love things for themselves. All that about bathing and food and bodies was a pose. He didn’t care – not like Jacques. And when a fly bit him, he just died out of carelessness. And so I wouldn’t call him substantial, as you do, unless you mean the schoolmaster side of him – the responsible practical fatherly man. He was a schoolmaster. For instance, he tried so hard to prevent all the friends whom he considered young and innocent from being enticed into your bawdy houses at Bloomsbury. Of course Bloomsbury disliked him; how could they help it, when he thought them so infinitely corrupt and sinister that no one (except himself) could be trusted to enter their purlieus and come out unsmirched. I don’t quite know why he thought Bloomsbury so devilishly poisonous, but he did – (and was it perhaps true that they weren’t very good for the-not-very- strong-in-the-head such as Margery Olivier? or the vain and credulous and cotton wool-stuffed such as Ka? What do you think? Oughtn’t women like that to go to church and be kept at their father’s coat tails until they are married and safe? Or doesn’t it matter either way?)

But Jacques wouldn’t have gone and died like Rupert. He, more than anyone I’ve ever known, did care about things and about living. Right up to the very end – to within a week of his death, he didn’t really want to die: though he said he did; or really quite believe that he was going to die, in spite of all the horrors he went through. It’s that that makes it seem so incredible that he’s dead. He lay there planning our journeys – journeys for me to go – journeys for Marchand – places I was to take Elisabeth to – dinners to eat (when the thought of food made him feel sick). No one but he could have lived so long in that state. And though he had lost nearly all possible physical pleasures, yet he could somehow taste the memory of them in his impotence with more force than Rupert ever could their reality in all his youth.

And yet, somehow life has seemed duller ever since Rupert died. And now it’s much duller still. I don’t mean the substance of things isn’t as strange as ever; only there’s no one to talk to about it. I suppose because I find it hard to get things into Language. You, a writer can talk to me, and (I think) I understand – but can I talk to you; do you understand? the things I care about are so dumb.